Indian journalist Rana Ayyub wrote an Op-ed in the Washington Post just before the 2019 general elections illustrating the rising exploitation of communal cracks by the ruling party in India. Citing the horrifying incidence of Akhlaq and Danish who were attacked by a blood-thirst mob, Ayyub went on to write some hard-hitting words: “In recent years, we have seen an explosion of ethnic and religious mob violence… that hate… is now all over the country that Modi rules.”

Commenting on the piece, Professor Shamika Ravi, a member of the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister of India, tweeted a graph of declining riots in India. She wrote,

“Anecdotes (however powerful) are not substitute to careful objective data analysis. And the data tell us that riots and tensions in India have been falling and very sharply from 1998 onwards. (The maximum riots were in 1981: 110361!) #KnowIndia #NewIndia”

This was the story of 2019. Some days back she tweeted an updated figure of riots in India declaring, “The country is most peaceful in 50 years.”

I recently did a piece on how reality might sometimes be completely different from our personal experiences, and data helps us to look at the broad picture. This is exactly what the professor seems to be arguing. In fact, the one thing that Ayyub’s op-ed missed was the data.

But, then the question arises, are we so wrong in judging the reality? Every day there is a new communal story in the newspapers and on the internet. Even if it is an exaggeration to say communalism has spiked sharply under Modi, it is impossible to believe we are the “most peaceful in 50 years”.

Let’s take a dive into the data.

Riots in India

The graph tweeted by Professor Ravi was absolutely correct. The data is taken from the yearly publication of the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). There has been a constant decline in riots in India since 1981. Yet, we need to know how riots itself are defined. Section 146 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) defines riots as violence committed by an unlawful assembly comprising five or more people. Thus, a fight by a group of six school-going students outside the school premises could be called a riot (legal experts could correct me if I’m wrong). In this regard, yes, India can be termed as the most peaceful in the last 50 years. But, the op-ed wasn’t talking about that, was it? What about communal riots in India?

In its latest publication, Crime in India 2021 (another thing worth noting is that we have come 7 months in 2023 and still don’t have crime data for 2022), NCRB has classified riots into 16 categories ranging from communal/religious riots to money disputes, water disputes, and power supply disputes. Communal riots constitute only around 1% of total riots in India. Hence, even if there’s a huge spike in communal riots, it won’t largely affect the number of total riots. And despite a 16-fold classification, ‘other riots’ has a share of more than 40% of total riots indicating small incidents mostly form the total number of riots in India. Originally, if the current government is accused of promoting religious enmity then why look at the number of total riots and not communal riots specifically? Only the professor might know the answer.

Nevertheless, there’s still one problem. This segregation of riots started only after 2014 by the NCRB. So, we can’t compare this government with the previous ones. Does that mean before 2014 we weren’t collecting data for communal riots in the country? No. Ministry of Home Affairs, in its annual reports, has been recording the number of communal incidents in India for many decades. Finally, can we now compare the communal incidents between different governments? I am sorry, but MHA stopped doing so after its 2016-17 report. With whatever government data we have, here’s the chart plotting communal incidence since 2005:

There are three years where both the NCRB and the MHA reported communal violence in India. And there’s a stark difference in their numbers.

In 2014, the year the Modi government came to power, NCRB finds 1,227 cases of communal/religious riots in India, the highest it has ever been recorded in MHA reports of the last decade. Whereas, the MHA annual report of 2014 finds only 644 cases of communal violence, the lowest in three years.

In 2015, the numbers are quite similar with MHA and NCRB recording 751 and 789 communal violence incidents in the year respectively.

In 2016, again, we saw a slight difference, however not as stark as in 2014, with 703 and 869 communal violence instances being recorded by the MHA and NCRB respectively.

There is a possibility that MHA only reports major communal occurrences, which could explain the discrepancy in the statistics, however, there’s no evidence of it.

In the eight Modi years, NCRB has recorded 723 communal violence incidents every year on average. In comparison, in the eight years before 2014, MHA reported 745 communal incidents every year on average. One might call it an “apple vs orange” comparison, yet this is the best we have.

If we take into consideration the world’s strictest lockdown that we witnessed in 2020-21, we can say communal riots in India were more or less equal in the first eight Modi years than in the eight years before that. Moreover, the graph has seen a consistent downfall except in 2016 and 2020. Thus, can we conclude that we have been slightly more peaceful under the current prime minister if not more? This leads to another question: Is one data point sufficient enough to make such a monumental claim? When my personal experiences conflicted with the statistical claims, I decided to dig deeper…

Mob Lynchings in India

The government made the decision to compile information on mob lynchings in 2017 and include it in the NCRB report. The NCRB collected the data on lynchings for the year but later decided not to print it in their report. The data collection was discontinued as the government found it “unreliable”. As of now, we don’t have any government data on mob lynchings happening in the country. It is important to note that mob lynching is different from riots. It is considered an offence against an individual rather than an offence against public tranquillity as in the case of riots. Even the case of Akhlaq and Danish mentioned by Ayyub would come under lynching and not riot.

There are a couple of private researches that give us a peek into mob lynchings in India. A report by the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) examines mob violence between January 2011 to June 2017 as reported in Indian media. The author writes,

“…mob violence was actually trending downward during the latter days of the UPA… [whereas] mob violence has been trending upward since the BJP came to power in the middle of 2014.”

The Centre for Study of Society and Secularism (CSSS) uses the same methodology of examining leading newspapers and compiling data for instances of mob lynching in India. Below is a chart of the data gathered by them.

The data shows a whopping 5250% rise in mob lynching between 2014 and 2019 and a sharp fall in the covid years.

Hate Speech Cases

One of the biggest changes we saw after prime minister Modi came to power is the hate speech given by ministers in the top leadership of the nation. From slogans of “Goli Maaro” by the current sports minister to call for the genocide of Muslims in a gathering attended by BJP leaders and others who are often seen with the prime minister.

Although there is no separate section on hate speech in the NCRB data, it can be gauged through the incidences of ‘promoting enmity between different groups that includes every act of promoting disharmony on the grounds of the birthplace, religion, caste, language etc.

In 2020, there were 1886 incidences of fostering hatred between communities, up from 336 cases in 2014—a 461% increase. Additionally, there was a steady increase in the number of cases between 2014 and 2020 and a modest decline in 2021.

Fake News

Fake news has been a serious problem in the recent past. The horrendous act of two women being paraded naked by a mob in Manipur was also the result of fake news. Expressing its concern, the supreme court asked the government, “Everything shown in a section of private media bears a communal tone. Ultimately, this country is going to get a bad name. Did you ever attempt to regulate these private channels?”

BOOM, a fact-checking organisation, analysed the 346 fact-checks they did during the pandemic between 26 January 2020 and 31 March 2021. In their report, it was found that more than 12% of their fact-checks were on communal claims. Furthermore, political fake news consisted of 4% of their fact-checks. Communal fact-check was the second largest category and just behind fact-check related to lockdown/restrictions (14%).

NCRB has maintained separate data on the cases of circulation of fake news since 2019.

The pandemic year saw a 214% rise in cases of fake news as reported by the police, and a 42% downfall in the subsequent year. Since there is no further segregation on the type of fake news, we don’t know the share of communal fake news.

Alt News, another renowned fact-checking enterprise, found out that 30.5% of their 462 fact-checks in 2022 were based on communal claims while 2.5% were religion-based.

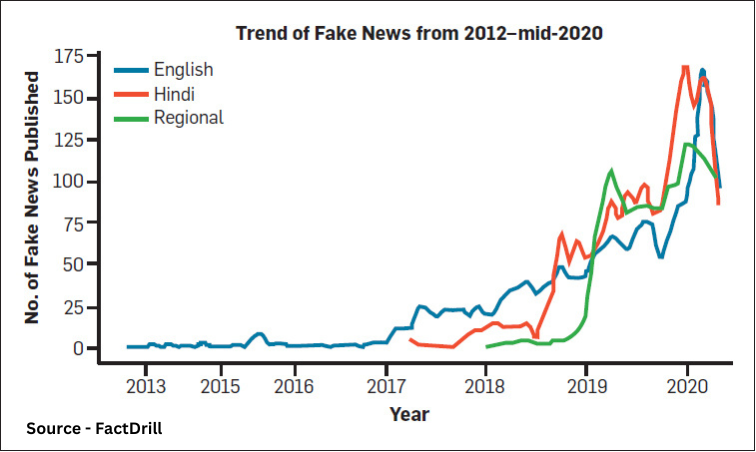

But, all of these are small studies with a limited time range. It doesn’t provide us with a comprehensive view of the condition of fake news in India. Therefore, members of the Precog Research Group at IIT Hyderabad came up with a bigger dataset of fake news being circulated in India through a project named FactDrill. It takes the fact-checks conducted by numerous IFCN-certified fact-checking organisations between January 2013 and June 2020.

As the graph suggests, fake news started to increase after 2017. Moreover, their research paper points out,

“The graph shows a steady increase in fake news production, with a major peak observed in 2019.”

Coincidently, 2019 was also the year of general elections in India– the election that was termed as most polarised by political analysts, where even the prime minister could be heard chanting religious slogans in his electoral speeches.

Hate Crimes

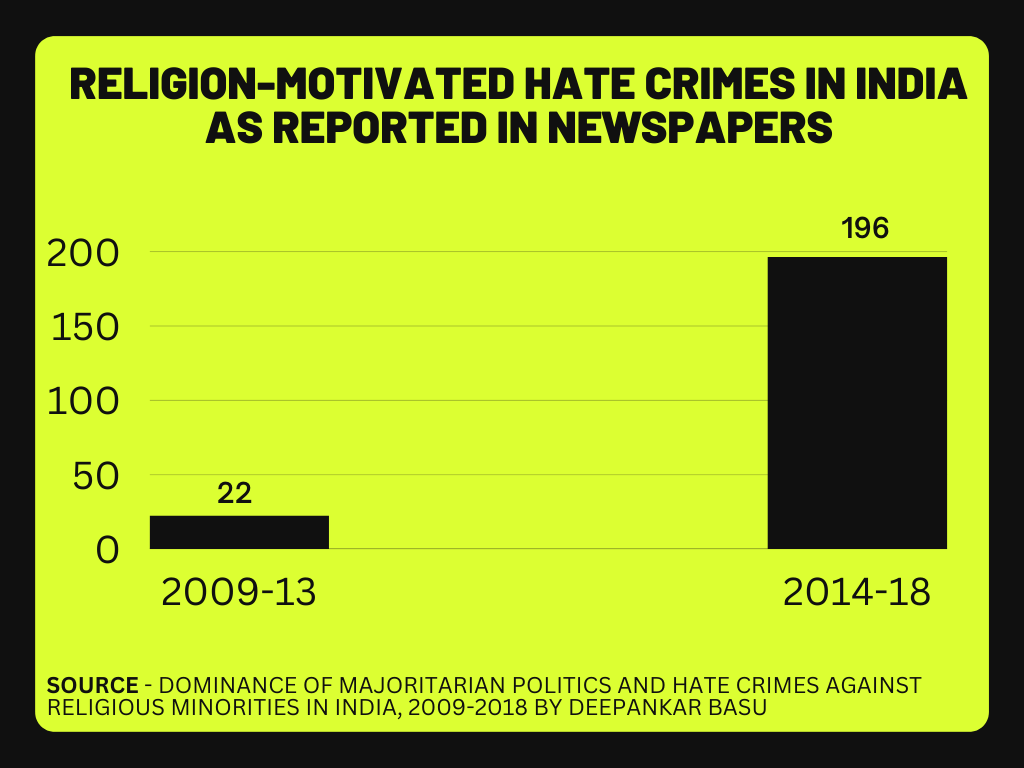

Citizen’s Religious Hate Crime Watch (CRHCW), an initiative by IndiaSpend, analysed the religion-motivated hate crimes in India as reported among major English newspapers between 2009 and 2018. Taking the help of legal experts, CRHCW looked at all the hate crimes, i.e., religion-motivated incidents which were considered punishable according to the Indian constitution. What they found out was surprising.

Deepanker Basu in his research paper divided these hate crimes before and after Narendra Modi was elected as the prime minister. He found out that a whopping 90% of hate crimes as reported in the newspapers were after the 2014 elections.

Conclusion

After thorough research using my limited intellect, I found out that while “communal riots” as defined by the IPC may not have escalated sharply, communal politics has. At a time when one of the Indian states has been burning for more than three months due to communal clashes, calling the country the most peaceful in the last 50 years is an irony of the highest degree. I will leave it here.